OpenMP internals part 0: a brief introduction to OpenMP

One of my goals with this whole blog thing is to write things down as I teach myself the internals of OpenMP. Before I start writing this up, though, I think I should at least write up a brief, high-level introduction for anyone who’s never used OpenMP before. There’s already plenty of “How to OpenMP” guides out there on the internet, so I won’t go into too much detail here. This guide from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory is a pretty good resource if you want to know more, though.

Before we get started though: this post, and probably the rest in the series, assumes some background computing knowledge. You don’t need to be an expert in OpenMP (that’s what this post is for!) but I’ll be assuming at least a basic familiarity with C and conceptual understanding of parallel programming (i.e. threads are a thing and running programs in parallel changes the execution flow. I’m going to put snippets of C code throughout the post as well, so you can use your favourite C compiler (I’ll be using GCC) to compile them and have a play around with OpenMP if you like (the post will still make sense even if you don’t, though). I’ll be using GCC on Linux, but they should also work on Windows and macOS (I haven’t tested either of these because I only have access to Linux systems. Feedback is very welcome here).

With that out of the way, let’s have a look at OpenMP.

What is OpenMP and why should you care?

OpenMP is a shared-memory multithreading framework aimed at high-performance computing (HPC) (e.g. computational physics, weather simulation), with support for C, C++, and Fortran. Strictly speaking, OpenMP is a specification, with multiple different implementations (similar to how there’s multiple implementations of the C standard library), but for brevity’s sake I’m going to call it a library from now on.

The basic idea is that OpenMP provides a set of high-level interfaces to allow scientific programmers to parallelise their programs without having to worry about the nitty-gritty details of thread management. OpenMP is designed to handle the kind of high-performance, numerically heavy code that I spoke about in this post, so it’s conceptually different to how most programmers tend to think of threads. For example, if desktop apps tend to use threads to concurrently handle really slow or blocking I/O: you might spin up a thread to listen on a network socket, while another one sits reading from the hard-disk so the program can go and do other things until the threads are finished.

That concurrency model is not how things work in OpenMP, since HPC programs are usually strongly CPU-bound, rather than I/O-bound. OpenMP gives us a relatively homogeneous thread-execution environment: OpenMP lets you split up your number-crunching (e.g. some linear algebra operation) into roughly evenly-sized chunks, and then distributes those chunks between the threads (we usually want one thread per physical core) to be executed in parallel. The net result of this is that we end up reducing the time it takes to complete the workload down to the time it takes to complete the largest chunk of work.

So far, none of this strictly needs a fancy library like OpenMP. Every modern operating system has it’s

own threading library (e.g. pthreads on Linux and macOS) and both C and C++ now have their own

threading constructs as part of their standard libraries, so you could just use those directly if you

wanted to. In practice, achieving a good parallel speedup is extremely difficult, especially if you try

to roll your own threading. In my experience, there’s three main hurdles to using raw threading

interfaces for HPC:

- You need to worry about creating and destroying threads, both of which come with a non-trivial performance overhead, as well as the fact that these APIs are just kind of fiddly to use.

- Handling synchronisation between threads is really hard. Most real programs eventually need to share data or resources between threads. Threads can execute in any order though, so you need to synchronise the threads’ access to shared resources otherwise you can end up with all sorts of hard to diagnose bugs (race conditions). But! It’s also really easy to tank your program’s performance if you’re not very careful with how you handle the synchronisation, so this takes a lot of effort to get right.

- Effective load-balancing (i.e. how do you split up the workload between threads?) is extremely important to extracting good performance, but is also really hard to reason about and implement. It’s common to end up with wildly differently-sized work chunks; without proper load-balancing you can end up with most of your threads sitting around twiddling their thumbs while they wait for one or two big chunks to finish. Bad load-balancing means you’re not making full use of your computational resources, which, again, will tank your performance.

OpenMP aims to automagically handle all of these concerns without troubling the developer with implementation details. I think this is a very worthy goal, since it’s unreasonable to require your average physicist to understand the low-level details of OS threading implementations in order to do their research - they’ve got physics to do! With that in mind, let’s take a look at OpenMP’s interface and how it tries to simplify parallel programming.

The OpenMP interface

The fork-join model

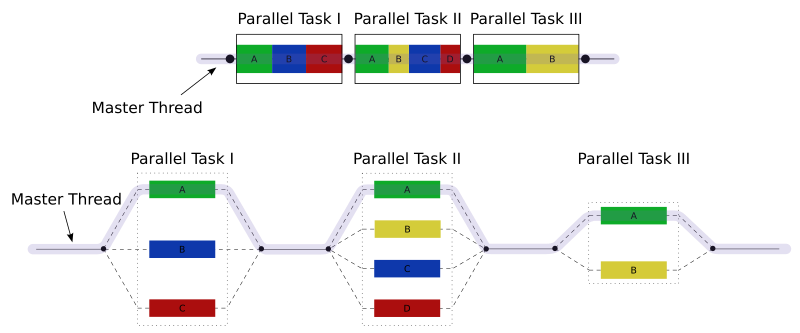

OpenMP’s multithreading is based around the fork-join model of parallelism, where we divide our code into serial and parallel sections. Our program runs sequentially until it encounters a parallel section, at which point it splits or forks into multiple threads, which all execute the section in parallel. Each thread gets a chunk of work according to some pre-specified distribution scheme. Once the threads have all finished a parallel section, they then re-join and the program continues on in serial until it hits another parallel section and the cycle continues. This picture I swiped from Wikipedia gives a really good graphical representation of the fork-join pattern (the letters “A” to “D” represent threads):

OpenMP provides a high-level interface for this fork-join pattern via a set of #pragma compiler

directives, which allow us to specify which sections of code should be run in parallel. It also provides

a series of work-sharing constructs (also via #pragmas) to specify how the parallel work should be

distributed between threads, as well as a library of functions to interface with the multithreading

environment.

How do we actually use it?

What does this mean in practice? Like all good tutorials, let’s start with Hello World:

#include<stdio.h>

#include<omp.h>

int main()

{

#pragma omp parallel

{

printf("Hello, world!\n");

}

return(0);

}

Save this block of code as hello.c and compile it with:

gcc -fopenmp -o hello hello.c

Then run with ./hello and you should get output similar to:

Hello, world!

Hello, world!

Hello, world!

Hello, world!

Let’s break down what’s going on here. First, we need to include stdio so we can print things, and

omp.h, which declares all of the OpenMP run-time functions. We’ll need these two headers for all of

the remaining examples, so I’m going to elide them from now on. Next, we get to the meat of the program:

the #pragma omp parallel directive, which will parallelise the block of code within the curly braces.

By default, OpenMP will use as many threads as there are physical cores on your machine, each of

executes the instructions in the parallel section. I have a quad-core machine, so the program prints

“Hello, world!” four times and then exits.

Sometimes OpenMP’s default choice will be sub-optimal, so it’s also possible to explicitly request

a particular number of threads, by setting the environment variable OMP_NUM_THREADS. In bash,

doing:

export OMP_NUM_THREADS=3

./hello

will run with three threads instead of four.

OpenMP assigns each thread an integer identifier, which we can use to make implement more complex

parallel algorithms or data structures. The two main functions which allow us to access these IDs are

omp_get_thread_num(), which returns the executing thread’s ID (which ranges from 0 to Nthreads - 1);

and omp_get_num_threads(), which returns the total number of threads taking part in the current

parallel region (which might be less than the maximum number of threads available).

The following program uses the thread IDs to print a different message for each thread:

int main()

{

#pragma omp parallel

{

int thread_num = omp_get_thread_num();

int num_threads = omp_get_num_threads();

printf("Hello from thread %d of %d!\n", thread_num, num_threads);

}

return(0);

}

Compiling and running this program should produce output like:

Hello from thread 0 of 4!

Hello from thread 2 of 4!

Hello from thread 1 of 4!

Hello from thread 3 of 4!

Notice that the threads do not necessarily execute in any defined order; if we were to run the same program again the threads would probably print in a completely different order. This non-deterministic execution is what allows for the performance gains from parallelism. Imposing a particular order on the threads would require them to communicate and synchronise execution, which comes with a non-zero performance overhead. This is actually a good rule of thumb for writing high-performance parallel code: synchronisation is expensive, so avoid it as much as possible.

Finally, let’s take a look at two of OpenMP’s work-sharing constructs, which is what allows us to

parallelise actual useful work. For starters, we can parallelise a for-loop via the #omp

parallel for directive, like so:

int main()

{

#pragma omp parallel for

for(int ii = 0; ii < 5; ii++)

{

int thread_num = omp_get_thread_num();

printf("Thread %d got iteration %d\n", thread_num, ii);

}

}

The parallel for directive splits the loop up into chunks of iterations, and assigns each thread its

own chunk to execute. If we compile and run this program, we’ll get something like:

Thread 3 got iteration 4

Thread 0 got iteration 0

Thread 0 got iteration 1

Thread 1 got iteration 2

Thread 2 got iteration 3

There are many more work-sharing constructs, each with their own specific use-cases, but all of them are

invoked via the same #pragma omp ... syntax. I won’t go into all of them here, but I’ll introduce more

of them later on as we go.

Each work-sharing directive, as well as the parallel directive, can take extra arguments via

a series of clauses. Again, there’s a lot of these, but I’m just going to focus on data-sharing

clauses.

OpenMP has a consistent data environment, which dictates how variables should be shared between threads. Each variable in the scope of a parallel region, but declared outside that region can have exactly one data sharing attribute, of which we’ll focus on two: shared and private.

First, the shared attribute does exactly what it says on the tin. Variables declared as shared are

shared between threads in the parallel region: the variable has the same value for each thread, and any

modification to its value in one thread will modify its value in all the other threads. For example,

each thread will print “The value of x is 3” in the following code-snippet:

int x = 3;

#pragma omp parallel shared(x)

{

printf("The value of x is %d\n", x);

}

However, if we were to modify the parallel region to:

int x = 3;

#pragma omp parallel shared(x)

{

x = x + omp_get_thread_num();

printf("The value of x is %d\n", x);

}

Then we get an output similar to:

The value of x is 3

The value of x is 6

The value of x is 8

The value of x is 7

Each thread changes every other threads’ value of x, but because we can’t expect threads to execute in

any order we get this confusing mess of results. As before, running this program again will produce

different output. This situation with multiple threads trying to modify the same variable is a

race-condition (specifically a data race) and is a notorious source of bugs in parallel programs.

Thankfully, OpenMP also has the private and firstprivate attributes to prevent this. Again, the

private attribute is fairly self-explanatory: each thread gets its own private copy of the variable,

and modifying one thread’s value doesn’t affect the other threads’ copy. Neat!

I’m glossing over a lot of details here, but the major take-away from this section is that the constructs and directives we’ve seen here are essentially declarative in nature. We use the interface (pragmas and library functions) to say what we want to do, and then leave it to OpenMP to figure out how to actually do it. I think this declarative nature is one of OpenMP’s biggest strengths, since it frees developers from fiddling with implementation details in order to focus on optimising their algorithm. At least, that’s the idea in principal, but there’s a few snags that prevent OpenMP from quite living up to its promise.

Things that bother me about OpenMP

In practice, OpenMP still requires a fair bit of low-level knowledge in order to extract anywhere close to the maximum possible performance from an application. This kind of limits its utility among its target audience of scientist coders - like I said, it’s really hard to justify learning the nitty-gritty of computer architecture when there’s papers to write and deadlines to meet.

For example, it’s actually really hard to reason about the ideal load-balancing scheme for a particular workload. Often, the amount of work and its distribution between, say, iterations of a loop won’t be known until runtime, so you have to either hack together a “pretty good” balancing scheme (which is no mean feat), or rely on OpenMP’s tools for automatic load balancing. The problem is, automatic load-balancing has a non-trivial overhead (get used to hearing that phrase, it’ll come up a lot) which can seriously degrade performance for certain workloads. How much overhead? What kinds of workloads? I hope you like vague and implementation specific answers, because that’s all there is.

This problem is not just a hypothetical, by the way - I ran into this exact issue multiple times when converting AMBiT to use OpenMP. The most irritating one involved a construct called task parallelism, which is a way of parallelising algorithms that don’t neatly fit into a simple parallel for-loop. Conceptually, it was the right tool for a couple of different subroutines in AMBiT (they involved chasing pointers through a complicated, custom data structure), but for some reason my particular workload triggered some strange performance pathologies. I wanted to use tasking, but the OpenMP overhead completely tanked the performance of that particular subroutine, and I still have no idea why.

I eventually found this paper, which suggested that the tasking overhead grows nonlinearly with the number of threads, which is really bad for performance (for context, AMBiT usually runs with 16 or 28 threads per process on our supercomputers). Even worse, optimising our subroutines to work around this overhead would have required a lot of implementation-specific knowledge (stuff like the OpenMP implementation’s task scheduling and data-sharing policies), which I have yet to find decent documentation on. In the end, our solution was “don’t use tasks”, which I think we can agree isn’t very satisfying.

And this kind of gets to the root of my annoyance with OpenMP. I don’t mind languages or libraries that require low-level knowledge to use effectively (I am a C++ programmer after all). But! If a language requires me to care about low-level stuff, then I don’t think it’s unreasonable to expect it to actually expose those details to me.

OpenMP does not do this. Its internals are maddeningly opaque and extremely poorly documented. Sure, there’s plenty of high-level tutorials floating around on how to use OpenMP, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen a comprehensive guide on what’s actually going on under the hood. This combination of needing to worry about the low-level stuff, but having no way of actually interacting with it is the worst of both worlds and I think it’s really holding OpenMP back.

This series of posts is my attempt at filling in some of those information gaps. I’m going to go through

the guts of GCC’s implementation of OpenMP, called libgomp, and see what the heck is actually going

on. For the next post, we’ll have a look at what GCC actually does when you use #pragma omp

parallel ... and friends. I’m still working through the implementation details and I’ll be writing the

rest of this series as I go, so come along for the ride and hopefully we’ll learn something cool!